Around 2020, a new round of turbulence began in the South China Sea with continuous friction events, yet there maintains overall peace and stability.

Since 2023, the Philippines has been provocatively challenging China in various areas of the South China Sea, intensifying the China-Philippines conflict and drawing renewed global attention to the situation in the South China Sea. Despite this, the actual situation is far less tense than what the media and the public imagine. Under the negative influence of increased US intervention and the ruling of the South China Sea Arbitration, other claimants have significantly raised their prices in the negotiations of the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea and other issues. Vietnam’s island-building activities and Malaysia’s unilateral oil and gas development activities are escalating. In 2025, the aforementioned issues and conflicts are likely to continue to ferment. The second term of Donald Trump will bring more uncertainty to the South China Sea situation. But overall, the South China Sea is expected to maintain a situation of competition without rupture and being heated without seething.

Image Source: Boundary and Ocean Affairs

Policy Trends of Major Countries Inside and Outside the Region

In 2025, the South China Sea policies of all major stakeholders influencing the situation in the region, including the US, will continue, despite possible changes and uncertainties in specific actions.

The framework of US policy on the South China Sea will be maintained

The US policy on the South China Sea has always been clear as it hopes something will happen every day but with no major incidents. It welcomes constant friction between ASEAN claimants and China in the region to expand its strategic layout in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait and increase pressure on China. However, the US is not yet prepared or determined to engage in military confrontation with China in the South China Sea, let alone to take risks for countries like the Philippines. The current framework of US policy on the South China Sea had been formed during Obama’s second term. Under the framework of great power competition with China and maritime strategic competition, the US seeks to contain China’s maritime rise by utilizing South China Sea disputes and its own capacity-building, maintaining a favorable power balance. Therefore, it takes sides on relevant disputes, strengthens its military presence in the South China Sea and its vicinity, and mobilizes countries inside and outside the region to oppose China regardless of truth and fact. This policy framework was roughly established around 2015 and has been fully reflected in documents such as the National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy and Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy issued in 2015. Going through Trump’s first term and the Biden administration, the framework has remained relatively stable in spite of significant differences in focus and approaches between different administrations. It is foreseeable that the current US policy on the South China Sea will likely continue into Trump’s second term.

The South China Sea is not a priority in Trump’s second term. Trump himself focuses on economic and trade issues, implementing contraction in global strategy to “Make America Great Again”(MAGA). His almost complete silence on the South China Sea issue throughout the entire campaign reflected that the topic takes nowhere in his agenda. Moreover, Trump holds negative views towards the ally system, which differs significantly from the Biden administration and the establishments, making it unlikely for him to respect the demands of allies like the Philippines. Therefore, the South China Sea issue is expected to receive even less focus in the US’s overall national security strategy and foreign relations in Trump’s second term. While, past experiences indicate that the situation in the South China Sea tends to be relatively calm when the US pays less attention, such as in the period from the end of the Cold War to 2009.

China's South China Sea policy will remain stable

China is the anchor of peace and stability and an important variable that influences the situation in the South China Sea. In the past decades, China has consistently emphasized "shelving disputes" and resolving conflicts through negotiations among the related parties. By emphasizing stability in the South China Sea, China is actually actively maintaining the status quo in the South China Sea dispute. For instance, China has reiterated publicly that “China has no intention of occupying Second Thomas Shoal, but only hopes that the feature can be restored to its natural state.” While China's policy remains unchanged, what has evolved is its capability and resolve to safeguard sovereignty and maritime rights. China's seemingly drastic actions are in response to provocations from the Philippines and Vietnam, among others.

In 2025, as long as the Philippines and others can exercise some restraint, China is willing to manage the issue through diplomatic means and keep the stability of the South China Sea. In fact, in 2024, China and the Philippines have eased the situation on Second Thomas Shoal and Sabina shoal through diplomatic channels.

The Philippines will continue to provoke but be constrained by its capability ceiling

Since the beginning of the current administration, the Philippines has had a plan to occupy and control the entire so-called West Philippine Sea. Since 2023, it has been comprehensively challenging China in various hotspots, including Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Shoal, Sandy Cay and Sabina Shoal, refusing to acknowledge any understanding or disputes with China. China’s strong countermeasures, especially resolute struggles at Second Thomas Shoal and Sabina Shoal, have forced the Philippine side to gradually recognize the real situation leading to a reduction in overall provocations. In 2025, under established policies, regardless of changes in US policy, the Philippines will continue to provoke China in various areas. However, whether in terms of operational capacity or determination, the Philippines is likely the weakest among the South China Sea parties, not to mention to compete with China. Unless the US directly intervenes to help, there is a ceiling on its ability for on-site infringements and provocations in the region, limiting the potential for major incidents and presenting more of a challenge in gray zone competition. In fact, over the past two years, the Philippines has essentially exhausted its tactics and postures for provoking China. In the future, there will be adjustments in location, pace, and intensity, but such provocations will generally be within expectations.

Vietnam and Malaysia will still strive to balance between infringements and bilateral relations

In recent years, overall relations between China and Vietnam and China and Malaysia have been stable and great, with frequent high-level exchanges. Generally, Vietnam and Malaysia are willing to control disputes and differences with China in the South China Sea through dialogue, negotiation and diplomatic channels, to prevent the South China Sea issue from affecting overall relations. However, both countries are strengthening their infringements in the region at the same time. In 2025, Vietnam’s island-building projects will enter a critical phase. As land reclamations finish in stages, Vietnam will expand its military equipment and troop deployments on the expanded features. Malaysia is attentive to China’s concerns, but will continue to push forward with oil and gas development in disputed areas in the South China Sea.

Major Risks

In 2025, the situation in the South China Sea will generally be stable, but there are some risks worth attention to.

Uncertainties brought by Trump’s second term

Although Trump does not care about the South China Sea and dislikes wars, he would like to use the South China Sea issue as a “card” to exert pressure on China in other areas such as economics and trade. For example, during his first term, though with little attention to the South China Sea issue, he tended to hype up military actions, overly politicizing “freedom of navigation operations” and Taiwan Strait transits. Such operations will undoubtedly exacerbate misjudgments between the two militaries and increase the intensity of confrontations during encounters. Additionally, Trump appreciates a corporate governance style, which sidelines the establishments, weakening the White House and the US National Security Council’s coordination of policies and actions, as well as control over strong departments like the military, indirectly granting unprecedented freedom to the military operational level. Currently, under intensifying political polarization, the long-term narratives of “great power competition” and the “China threat” as well as the anti-China political correctness, there is a possibility that opportunists within US policy and action branches could deliberately create incidents between China and the US for their own benefit. Furthermore, the US military in the Western Pacific has been in a state of excessive deployment and fatigue for a long time, leading to a decline in professionalism and an increasing risk of accidental incidents with Chinese vessels and aircraft.

Maritime and air frictions between China and the Philippines

In 2024, there were multiple incidents of water cannon and collisions between China and the Philippines. As long as the Philippines continues its provocations, such incidents will be unavoidable. Challenging China in the entire so-called “West Philippine Sea”, the Philippines is increasing the frequency and intensity of provocations in Reed Bank and Scarborough Shoal after setbacks at Second Thomas Shoal and Sabina Shoal. As China strengthens its control over Scarborough Shoal, the Philippines’ counterattacks become increasingly aggressive. Recently, the Philippines has significantly increased its aerial provocations towards Scarborough Shoal. The risk and uncertainty of aerial encounters, especially confrontational encounters, are much higher than those of maritime ones. If the Philippines persists in infringing, China will have to take corresponding measures. Once a friction or collision occurs, the consequences will be much more serious than a collision at sea. Using mostly single-engine turboprop light general-purpose aircraft in its operations, the Philippines is fragile to accidents during frequent maritime activities with weak capabilities to withstand complex maritime environments. Furthermore, Philippine military aircraft operate with transponders switched off throughout operations, posing higher potential safety risks. In the event of such an accident, based on the Philippines’ past practices and habits, China will certainly be blamed, leading to another round of “victim-playing” and diplomatic propaganda.

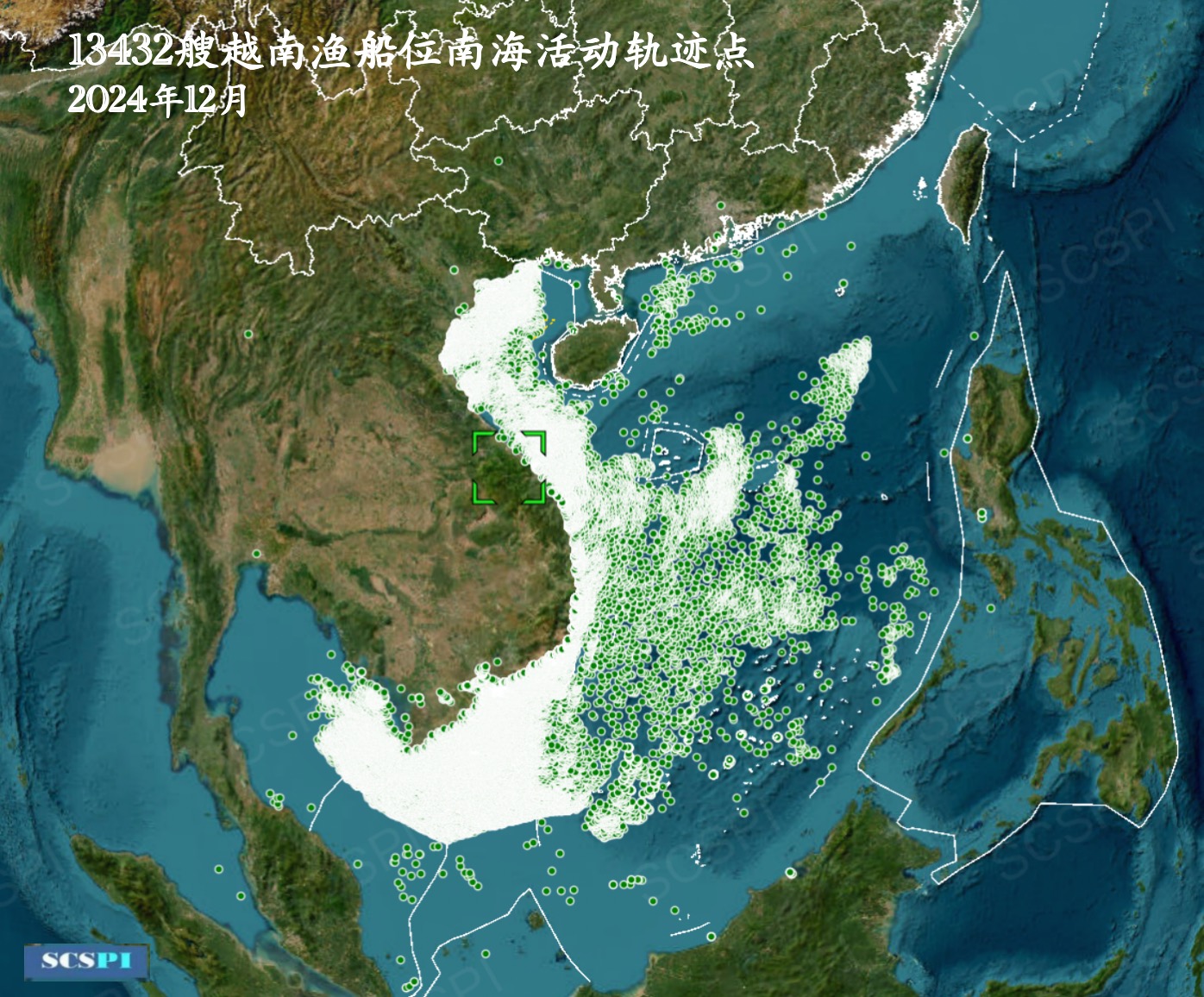

Accidental incidents involving Vietnamese fishing boats

Vietnamese fishing boats have become a major nuisance in the South China Sea. With official support and encouragement from Vietnam, the fishing boats, not only frequently intrude into the territorial and internal waters of China’s Paracel Islands but also extensively infringe upon the internal waters and territorial seas of Hainan Island, Guangdong, and Guangxi, exceeding 3,000 annually. Vietnamese fishermen operate aggressively, widely using explosives, dynamite and toxic substances. They are unruly, often violently resisting law enforcement and frequently engaging in intense conflicts with law enforcement forces from almost all neighboring countries in the South China Sea. Additionally, being adept at “playing the victim” and causing trouble, they can easily spark diplomatic friction between the two countries. In 2024, despite the overall positive atmosphere in Sino-Vietnamese relations, the Vietnamese side lodged several protests with China over fishing vessel issues. Frictions between Vietnamese fishing boats and Chinese fishing boats and law enforcement forces occur almost daily, posing a high risk of accidental incidents.

In the South China Sea, three types of contradictions—maritime disputes, geopolitical competition and rules and order games—will persist in the long term and continue to escalate. Meanwhile, with an increasingly strengthening influence and power to control the situation, China may lack the ability and conditions to resolve the issues in the short term, but is competent to manage the situation. Although the situation in the South China Sea is expected to remain tense in 2025, it is unlikely to be worse than in 2024. The more intense and furious the situation becomes, the more important it is to maintain calm and rationality. The movements of parties like the Philippines and the US in the South China Sea still need to be highly vigilant and taken seriously. However, exaggerating the tension is not conducive to a normal response and countermeasure. With China’s current strength and capabilities in the South China Sea, as long as there is firm determination and will, other claimants like the Philippines are unlikely to succeed in on-site infringements and provocations even with external support. Excessive worry about risks and uncertainties is not advisable. While it’s necessary to be vigilant against risks, there is no need for excessive tension. Even in the event of unexpected incidents, China has a significant capacity for management and control.