On April 3rd, the SCSPI delegation visited Manila and attended an open forum titled “7th Bilateral Consultations Mechanism (BCM) on the South China Sea (SCS): PH-CN Relations Against Stress on the SCS” with Philippines local media, organized by the Asian Century Philippines Strategic Studies (ACPH).

Hu Bo: Three Factors Affecting the Situation in the South China Sea

Good morning, everyone. Nice to be back to Manila again. Today, my colleagues and I from China will introduce our points and views on the situation of the South China Sea, with some Chinese perspectives. We do not represent the Chinese government, and I think you are very familiar with China’s position on the South China Sea. Thus, we would like to share our views on this issue candidly and frankly as scholars and Chinese.

In the past few years, we have seen that great power competition, maritime disputes and rules building are becoming the three major factors affecting the situation in the South China Sea. Let's take a look one by one:

Power Competition

As we all know, the US treats the South China Sea as the main battlefield for strategic competition with China. Maintaining a balance of power in favor of itself rather than the freedom of navigation or the security of regional countries, is at the root of all US actions and polices in the region. In this context, China has no choice but to respond. In addition to the well-known strategic opposition, interactions and risks at the tactical level between the US and China are also rapidly escalating. Of course, the situation is not as dangerous as the media and the public see it. In the South China Sea, despite the growing competition as well as sea and air encounters between the two militaries, it is worth noticing the fact that most of the encounters, more than ten times per day and thousands of times every year, are safe and professional.

China and US military aircraft encounters Source: PLA Southern Theater Command

In sum, the United States and China have entered an action-to-action cycle in the Western Pacific including the South China Sea, and in the short term, neither side is likely to make substantive compromises. Now, the choice of third parties, including Southeast Asian countries, is more and more an important variable in the strategic competition between the United States and China. If Southeast Asian countries do not choose sides in the US-China strategic competition or do not support that, the deteriorating trend of US-China strategic relations will be alleviated to a great extent; On the contrary, it will further fuel the flames.

Maritime Disputes

In terms of maritime disputes, the status quo is increasingly difficult to maintain. Some claimants adjust their maritime claims according to the South China Sea Arbitration and ask for a much higher price in the interaction with China. Stimulated by US intervention and the South China Sea arbitration, unilateral oil and gas development activities in disputed areas of the South China Sea are also intensifying. As for the status quo of occupations on the features of the Spratly islands, although it has been maintained in general, there are also some bad signs. There are rumors here that China will occupy some new uninhabited features, but as far as I know, Beijing has no such plans. Reversely, with more and more Philippine official statement declaring to expel China from the disputed waters, West Philippine Sea in Philippine saying, China has reason to concern that the Philippines will occupy some uninhabited features like Second Thomas Reef, Sandy Cay and Whitsun Reef. If this happened, it would directly overturn the consensus of the DOC and the peace and stability of the South China Sea. Yes, more and more Chinese military and fishing vessels are showing up in disputed areas, however, this is what other claimants are doing, and China's policy of shelving disputes has never been changed. And, China’s South China Sea claims have a very long history, and they didn’t emerge in the recent years. Every claimant including the Philippines has the right to strengthen its claim, but also need to consider the history and reality of the disputes.

Rules Building

For the sake of the peace and stability of the South China Sea, China and ASEAN member states plan to form an effective set of rules and order in the South China Sea. Although the process of implementing the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and the COC consultation among China and ASEAN countries are not satisfactory, the communication itself is still important. This is the ASEAN way by Consensus, which is the only possible path for confidence/rules building in this region. No matter what the final outcome of the COC consultation is, COC is not the end of the rules building in the South China Sea.

Last thing I want to say is, maritime disputes are not the whole of China-Philippines relations. I sincerely hope that Beijing and Manila can manage the maritime disputes to an acceptable level, though which cannot be solved in the foreseeable future.

Yan Yan: China-Philippines Relation and the SCS: Managing Crisis for a Common Future

China and the Philippines established formal diplomatic relations in 1975. Relations between the two countries have been predominantly warm and cordial over the past 48 years. Especially in the past six years, China and the Philippines have not only dovetailed through the Build Build Build (BBB) program and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but also launched nearly 40 government-to-government cooperation projects in various fields, including agriculture, trade and economy, energy, infrastructure, science and technology, and humanities. The bilateral trade volume between China and the Philippines has doubled, and China has steadily become the Philippines' top trading partner and the top source of imports, and a comprehensive strategic cooperative relationship was formally established during President Xi Jinping's state visit to the Philippines in November 2018.

However, territorial dispute and maritime jurisdiction dispute in the South China Sea, have plagued bilateral relations over the years. With the awareness of the dispute will not be able to solved in the near future, the two governments have dedicated to manage the differences and promote maritime cooperation. For example, China, the Philippines and Vietnam entered into a Joint Maritime Seismic Undertaking Agreement (JMSU) in 2005; China and the Philippines established the Bilateral Consultative Mechanism (BCM) in 2016; the two countries also established Joint Coast Guard Committee in 2017. During President Marcos’s January visit to China, he has also stated “to settle problems in a friendly manner and seek to resolve those issues to the mutual benefit of the two countries”.

China's President Xi Jinping and Philippines' President Ferdinand 'Bongbong' Marcos Jr. during a welcoming ceremony in Beijing Soucre:BBC

To manage the dispute for a future healthy bilateral relations, there are several things the two nations could consider. First of all, on the multilateral level, China and the Philippines are both negotiators in the Code of Conduct. The objective of the COC is to create a favorable environment for the disputing countries to resolve the disputes in the future and to manage the air and sea crises before the final settlement of the South China Sea issue to ensure the peace and stability of the South China Sea region. Both are involved in the negotiation process, China and the Philippines should work together to reach a substantive and effective COC in the coming years.

Second, bilaterally, the Bilateral Consultative Mechanism (BCM) established in 2017 continues to be a practical and feasible way to share concerns and convening technical working groups to work on maritime cooperation proposals. On March 24th, the 7th BCM was held in Manila. It is the first one in President Marcos administration. It should continue to serve as a confidence-building measure that tackles maritime issues between the two.

Third, in order to prevent incidents and manage maritime and air crises, China and the Philippines can establish hotline between defense departments and maritime law enforcement agencies. The establishment of a direct communication channel between China and the Philippines, the establishment of a hotline for fisheries emergencies, maritime search and rescue, and a communication and coordination mechanism for emergencies can further strengthen the dialogue and communication between the maritime-related departments of the two countries.

In all, the South China Sea dispute should not be in the way of future cooperation between the two. On the one hand, the maritime dispute between China and the Philippines, should not be linked to the US-led geostrategic competition with China. On the other hand, the bilateral trade and economics, high-level exchanges, people-to-people exchanges, and the synergy of BBB program with BRI, are beneficial to both sides and should be the solid foundation for future bilateral relations.

Lei Xiaolu: Resolve the Disputes in the SCS through “Asian Way”

Last year remarks the 20th anniversary of the conclusion of DOC, what impressed me most is the joint effort of China and ASEAN members to set the regional rules for the stability and peace of the region on the basis of consensus and accommodating the comfort levels of all parties, which is summarized as “Asian Way” which provides the fundamental guide for countries to pursue development through cooperation, by H.E. Li Qiang, Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, in his speech at the Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference on 30th March. Concerning some unique characters of the disputes between China and coastal states in the SCS, it is the time for China and other disputants to be more confident to resolve the disputes by using the Asia Way to create new models and framework and methods.

The disputes between China and other disputants in the SCS can be categorized into two parts. The first is the dispute concerning territorial sovereignty over the maritime features and the maritime disputes. The territory claims over the maritime features are not to the single island but to the group of islands as a single unit in the South China Sea by China, Vietnam and the Philippines. However, the South China Sea Arbitration Award derogates the territorial claims by deciding some of the maritime features into LTEs, which “cannot be appropriate”. It is not possible to get a durable solution without paying special attention to the Asian practice in the long history.

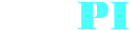

Second, relating to the dispute, China and ASEAN members will have different understanding and positions on the activities in the SCS. For example, the joint development of the Oil and Gas in the Reeds Bank. For China, the SC72 is located in the disputed sea area pending maritime delimitation, while the Philippines holds that the area is within its EEZ. In 2018 MOU, both of the parties agree that the development will be “without prejudice to the respective legal positions of both governments.” How to promote a joint development when the two parties disagree on the maritime entitlement claims would be another new problem that the two parties will overcome. There is no precedent for us to follow.

The location of drilling activities in the Reed Bank Source: the Philippines Government

Concerning the rights of other countries, especially the US and other non-coastal states, according to international law, China and ASEAN members cannot create any obligation for the third states which is not a party to the COC. The special interests of the other countries are not the main subject matter of the COC, and will not be influenced by COC. The other states should respect the joint efforts of China and ASEAN members to manage their potential conflicts and disputes, not to make the object and purpose of the COC meaningless by increasing the risk and uncertainty to peace and stability of the region.

The rule-based maritime order would be based on the common understanding of international law of the countries in the region, not posing one’s understanding or standard to others. In the SCS, China and the ASEAN members have the right, competence, and capacity to establish the regional framework of rules to promote the prosperity and peace in the region.

Zheng Zhihua: How should we define the South China Sea dispute and Sino-Philippine relations?

Should we allow the South China Sea dispute define Sino-Philippine relations? Should we let the Sino-American great power rivalry define Sino-Philippine relations? Should we allow external forces to use the South China Sea dispute as a tool to undermine peace and stability in the South China Sea?

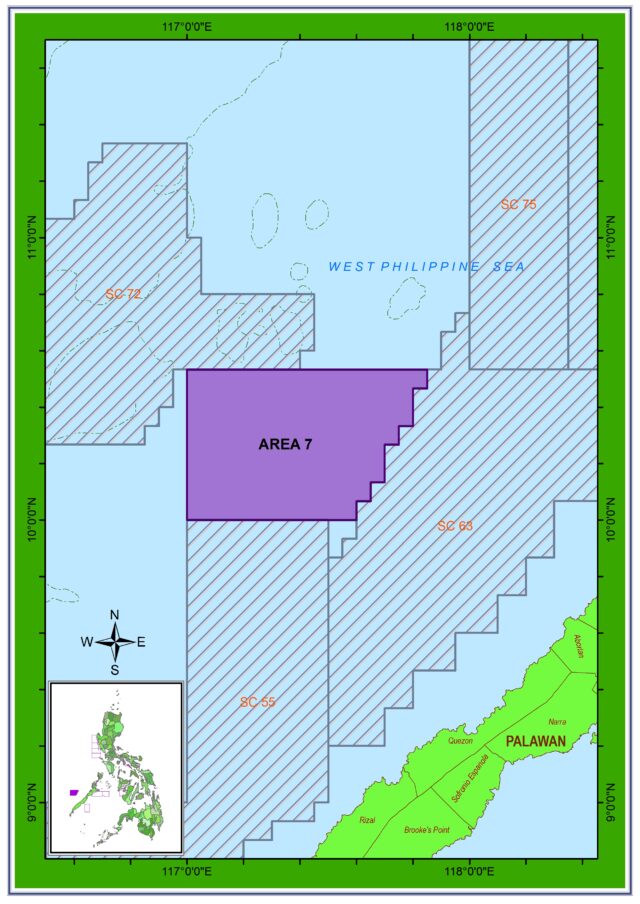

First of all, I think we should give a quick review of China’s South China Sea claim. Where does it come from and how should we see it? Does it become more aggressive and assertive as some Western media portray it? If we compare it to China's sovereign claims in the South China Sea 90 years ago, is China’s claim fundamentally different? China's claims in the South China Sea are essentially a responsive, defensive move rather than an expansionist one. Back in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, British, France, Japan and other external powers continued to expand their presence in the South China Sea, encroaching on the relevant South China Sea islands and reefs. Chinese government (then KMT government) was forced to respond to this, for example, in 1935 the KMT government published a map of the islands in the South China Sea in protest of the occupation of the nine small islands in the South China Sea by France at that period, clarifying the scope of China's territorial sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, in effect to protest the illegal occupation of the islands and reefs by Western colonialists.

The 1935 map of Chinese Islands in the South China Sea

During World War II, Japan occupied all the South China Sea islands and reefs, and the South China Sea almost became Japan's inner lake. When the KMT government recovered the islands in the South China Sea after Japan's defeat and published a map of the locations of the islands in the South China Sea in 1947. These moves were also responsive and defensive. By this time China's claim to the South China Sea was basically finalized, and after the founding of the People's Republic of China, the South China Sea claim was basically continued, as it was during the KMT period. If we compare the scope of China's claims today with the claims to the four island groups in the South China Sea under the KMT government 70 or 80 years ago, they are practically the same. Therefore, it is not historically accurate to portray China's claim as an expansionist one.

The current narrative of South China Sea history has adopted an extreme Eurocentric perspective, with a strong bias and lack of basic sympathy for the history of Asia, resulting in a very narrow and even diametrically different interpretation of the history of the South China Sea, deepening the rift between China and its neighboring countries. Some western research mainly based on English newspapers in the first half of the twentieth century, the interpretation is deeply fragmented, which even violates some basic historical common senses. With regard to territorial and maritime disputes, a relatively objective research conclusion can be reached only after weighing and comparing the evidences given by all the States concerned. Perhaps this requires the joint efforts of historians from all relevant claimant countries around the South China Sea to promote common research and enhance a common understanding of the history of the South China Sea.