On May 11, 2022, Presumptive President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. won by a landslide in the recent Philippine elections. He received an overwhelming mandate to govern the 112 million Southeast Asian nation, be the commander in chief of its 140,000 strong armed forces, and the chief architect of its foreign policy. The incoming 17th head of state of the republic will be joined by his running mate, presumptive vice president Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of the incumbent President Rodrigo Duterte. The duo will be aided by six of their senatorial slate, as well as other solons seen as close allies, who were in the top twelve of the vote tally. This puts his administration in a good position to chart the country’s direction in the South China Sea flashpoint.

Philippine Presidential Election, 2022 Source: AP Photo/Aaron Favila

Marcos Jr.’s policy towards the South China Sea will likely be shaped by three crucial factors: 1) the legacy of his father, the late strongman Ferdinand Sr.; 2) the appeal of his predecessor’s policy; 3) the emergence of the South China Sea as a hotspot for great power contest. A second Marcos leadership is likely to temper sharp pendulum swings in Philippine policy towards its big neighbor and the intractable maritime tiff.

The father was invested on the South China Sea and so does the son

In 1975, the elder Marcos established the country’s official relations with Beijing, the semi-enclosed sea’s biggest claimant. Three years later, he formalized his country’s claim on the Spratlys and its surrounding waters through Presidential Decree No. 1596. Under his watch, the country built an airstrip in Thitu Island, the second-largest land feature in the area, and occupied other nearby rocks and reefs. These became the nucleus of the country’s smallest town of Kalayaan, which to this day remains a constituent part of the province of Palawan, the nearest landmass in the area. Marcos Sr. thus played a central role in laying the foundation for Manila’s jurisdiction on these Dangerous Grounds. He also opened doors for engaging foreign energy companies keen to explore hydrocarbons in the waters’ seabed. At the same time, he also created the basis for diplomacy between the two sides, crucial in handling the disputes he might have anticipated.

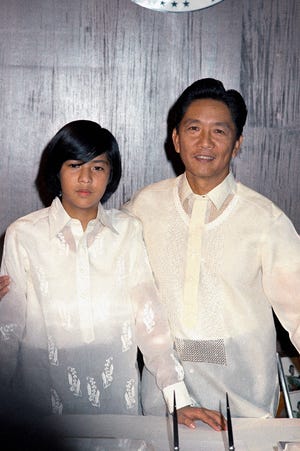

Thirty-six years later, his son is now at the cusp of securing the highest post in the land. He is expected to defend the country’s position in the troubled waters and exercise dialogue with Beijing (and other claimants) which his father made possible. The territorial and maritime row is thus national and, at the same time, personal for the younger Marcos. He is invested in this issue as his father was.

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and his father Ferdinand Marcos Source: AP Photo/Jess Tan Jr,

Taking off from where his charismatic predecessor left

Secondly, Bongbong is likely to sustain his predecessor's policy towards China and the South China Sea. He is likely to support the continued infrastructure upgrades in Philippine-administered features to improve the living conditions of Filipino settlers and troops stationed in the Kalayaan and fishers operating in the area. The proposal to turn Thitu Island into a logistics hub to reduce the turnaround time for resupplying provisions to nearby outposts may also earn his favor. He will greenlight stepped-up patrols to protect the country’s maritime and resource interests in the area. Duterte’s golden age of defense spending, which helped modernize the country’s navy, air force, and coast guard, will continue to gather pace. On the legislative front, Marcos is likely to push for the fast tracking of relevant bills that will define the country’s maritime zones and archipelagic sea lanes, which bears on Philippine sovereignty, sovereign rights, and national security.

Rodrigo Duterte and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. Source:Marcos Facebook

At the same time, a Marcos 2.0 government is expected to carry on Duterte’s engagement with China to expand over-all ties, notably in the economic domain, and build trust and confidence as bases to address difficult aspects of the relations. For him, diplomacy should not be allowed to fail as war is not an option. The Bilateral Consultation Mechanism (BCM) which was established and convened six times over the last six years will likely be sustained as a key high-level platform to sort out differences over the flashpoint. From the vice-ministerial level, it may logically go down to the inter-governmental technical working group stage, where details of a possible joint development for offshore oil and gas may be fleshed out. BCM can also be a venue to discuss maritime incidents and other pressing or emerging issues related to the maritime spat. BCM may get more traction from high-level official visits at the presidential and ministerial levels. Bongbong will actively commit the Philippines in negotiations to conclude at the soonest possible time a binding and effective Code of Conduct which is hoped to mitigate untoward maritime incidents.

On the ground, a joint committee of the Philippine and Chinese Coast Guards may become more institutionalized, and hotline communications and crisis management mechanisms should be given full play. Naval and coast guard diplomacy between both sides may grow, and interaction among these frontline maritime agencies may engender more professional conduct and less untoward sea mishaps. Unfettered access to traditional fishing grounds in Scarborough Shoal and elsewhere in the Spratlys is a low-hanging fruit that both sides can and should quickly work on. Bongbong considers this as one of his priorities. Co-administration and possible joint patrols in the vicinity of the Scarborough Shoal, including inside the lagoon, is another area that may be explored. Negotiations toward a coordinated fishing ban in the South China Sea will be a welcome replacement for unilateral measures that periodically engender pushback and hostility from other claimants.

Like his forerunner, Marcos Jr. will continue to assert the landmark 2016 arbitration award in domestic and foreign venues. He may be tempted to downplay the judgment given China’s firm objection to it, but local and international pressures may dissuade him from doing so. Unlike Duterte, the younger Marcos may eschew making off-the-cuff remarks that question or diminish the ruling’s value. There will be less bombast, bluster, and theatrics, and differences will be handled discreetly through proper diplomatic channels or high-level talks. In contrast to Duterte, who has to aim for a soft landing, Marcos enjoys a well of cordial ties built on the back of his precursor’s amiable and pragmatic policy towards the country’s largest trade partner. Duterte, back in 2016, had a harder time. The former Davao City mayor has to deftly navigate his way as the historic award came out just two weeks after his inauguration, giving him his first serious foreign policy litmus test. This legacy of amity and Marcos Sr.’s contribution to establishing official ties – which is never lost to Beijing – present both sides with a sturdy container that can weather tough conversations.

Asserting autonomy in the age of great power rivalry

Finally, the recognition that the South China Sea has become a theater for major power rivalry will compel Marcos Jr. to double down in asserting Philippines’ agency and autonomy. In one presidential debate, he said that: “No matter what superpowers are trying to do, we [referring to Filipinos] have to work in the interest of the Philippines. We cannot allow ourselves to be part of the foreign policy of any other country and we have to have our own foreign policy. So again whatever the superpowers do, we, having a highly strategic geographical location in the world, have to walk that very, very fine line between these great powers where we are in between. If they sneeze at the same time, we disappear from the map, and that is something we always have to keep in mind.” To avoid getting squeezed between the clashing titans, he will refrain from involving the United States in the country’s disputes with China. This means that Manila will not approach Washington to broker or mediate over a maritime incident which the past second Aquino administration did in 2012. In one interview, he said that such an act is only bound to fail as it puts two competing protagonists together.

Like Duterte, he will also distance from US-led joint patrols in the South China Sea. He may also decline joint sea drills unless perhaps the whole of Southeast Asia gets on board. It must be remembered that in 2019, ASEAN and the US held joint maritime exercises on the heels of an earlier ASEAN-China naval exercises the year before. Like other regional leaders, the new president may also keep an arms-length on overly security-oriented configurations like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) or the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) arrangement. It is not unlikely for him to factor in possible reaction and security concerns of China and fellow ASEAN members in military agreements and activities with the US. This is aimed at avoiding overly antagonizing its primary economic partner and unsettling close neighbors. To this end, it will be interesting to follow what constraints he will put on the alliance to avoid upsetting ties with Beijing or disturbing the precarious and fast-shifting regional balance of power.

This said, Marcos Jr. will remain open to working with the country’s 70-year-old treaty ally to develop the country’s maritime capacities. The Philippine military has deep and well-entrenched linkages with its US counterpart, and no president can easily upend that. Duterte realized this, and Bongbong is no stranger to it. Unlike his mercurial precursor, differences with the country’s security ally will be less advertised publicly. He said that the special relations with the US are not something the country can treat casually and be so cavalier about. He added that the alliance is deeply etched in the Filipino psyche, and the idea and memory of how Washington fought with its former colony during World War II provides a deep anchor for enduring ties. Bongbong is also likely to pursue Duterte’s defense diversification, expanding the country’s pool of security partners beyond the US, Japan, Australia, and South Korea to include India (especially with the BrahMos missile acquisition), France (possibly on acquiring submarines) and even China and Russia. Beijing, for instance, donated RMB 130 million worth of non-combat equipment to support the Philippine military’s humanitarian assistance and disaster relief work.

China donates RMB 130 million worth of military equipment to Philippines

Source: Department of National Defense, Philippines

In sum, the second Marcos administration is expected to inject much policy continuity in dealing with the South China Sea. Bongbong can leverage his father’s role in laying the cornerstone of the 47-year-old official ties and Duterte’s friendly policy in the last six years to set ties on a good footing. Such goodwill can serve as a robust ballast to allow the two countries to insulate broader ties from the turbulence brought by the longstanding row.